Promoting inclusive education management in Nigeria

Fatima Aboki and Helen Pinnock

SBMC members listen to children’s ideas for improving their school © Sandra Graham

Nigeria has the most out-of-school children worldwide: 8.7 million. Children are excluded because of poverty, gender, disability, geography, language, albinism and nomadism. Education has been ‘one size fits all’: teaching is not differentiated for children’s diverse learning needs; communities and teachers have not helped children facing difficulties come to school; and corporal punishment, conflict and sexual harassment keep children away.

Since 2009, the Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria (ESSPIN), funded by the UK Department for International Development and managed by Cambridge Education, has been supporting change towards an inclusive education system in six of Nigeria’s poorest states. Different strategies have been piloted at policy, school and community levels, to test which approaches are relevant to local capacities and priorities. Here Fatima and Helen summarise some of ESSPIN’s achievements.

ESSPIN developed these indicators to measure progress on inclusive education:

- Each state has a clear policy on inclusive education that outlaws all forms of discrimination and promotes learner-friendly education;

- There is support for civil society to give voice to excluded groups in planning and budgeting;

- Data on out-of-school children is collected and available at state and local government levels;

- Expenditure on access and equity activities in schools is predictable and based on the medium- term sector strategy;

- Local education officers receive information and respond to community access and equity issues.

ESSPIN provides resources, advice and training to help state education systems make progress in each area. School infrastructure has been improved to expand access; different types of schooling have been offered; communities have been mobilised to help children come to school; and teaching practice has improved.

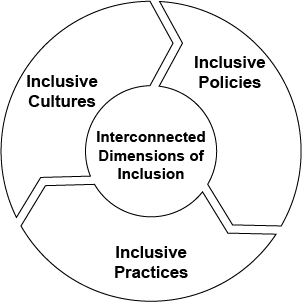

Three elements of improving education access and equity have been explored (see diagram):

Supporting inclusive culture

ESSPIN’s inclusion work has strengthened school-based management committees (SBMCs). This has built a culture of shared accountability for education between government and communities, and put inclusion at the centre of school improvement.

SBMCs are formed from a cross-section of the community, organising educational support and bringing community education priorities to government. Federal SBMC guidelines existed before 2009, but few SBMCs were active. Using a process designed by Save the Children, ESSPIN supported state governments to adapt the federal guidelines into a state SBMC policy. Government set up partnerships with civil society, using staff from local government and civil society organisations (CSOs) in a ‘buddy system’ to activate, train, mentor and monitor SBMCs.

Regular visits for training and mentoring from the CSO-government partnership encourage SBMCs to support children’s enrolment, feeding, clothing, equipment, and daily attendance. SBMC training covers child protection, disability, gender, inclusive education, monitoring, conflict resolution, child participation, fundraising, project management and financial accountability. SBMCs monitor the school environment and teachers’ attendance and behaviour.

SBMCs have activated the community and donors to help children attend school. Children with disabilities have received wheelchairs, food and clothing; families have been encouraged to keep daughters in school; and SBMCs have recruited teachers who speak the languages of minority children. SBMCs have prepared inclusive school development plans and successfully lobbied government for resources to expand and improve schools.

Between 2010 and 2015, 10,442 SBMCs were supported like this. Governments in ESSPIN- supported states and across Nigeria are using their own funds to scale up the approach, contracting CSOs for support.

In 2013 state governments introduced a monitoring system to document the benefits of SBMC support, motivating government to keep training SBMCs. Local education staff use templates to collect data on how many children (boys and girls, and with disabilities) have enrolled as a result of SBMC action, and estimate local children still out of school. The reporting system provides information on challenges faced by SBMCs, so that government can respond with policies and resources. Visiting CSOs also collect information for use in advocacy.

Advocating inclusive policies

In Lagos, during visits to SBMCs, CSO and education staff saw how children with disabilities were excluded from school. They then set up a policy forum for government and civil society on disability and inclusive education. ESSPIN funded the forum and trained CSOs in presenting evidence. The forum meeting led to state commitments to generate an inclusive education policy, for which ESSPIN offered advice.

Through similar processes, four ESSPIN-supported states have inclusive education policies, with actions targeting disadvantaged children and marginalised groups. States have capacity development plans for education staff to ensure implementation of the policies.

ESSPIN has also supported out-of-school surveys in three states to gather numbers and reasons for non-attendance. In response to this information, state budget plans are allocating resources more effectively according to need.

Promoting more inclusive teaching practice

As well as training on child-centred methods, a network of visiting school support officers, set up in local authorities, encourages teachers to include diverse learners. Work is being done with training and school leadership bodies to improve policies, curricula and assessment for enrolment and inclusive teaching.

The latest Composite Survey to measure outcomes shows that ESSPIN-supported schools perform better than control schools in several areas. These include school inclusiveness (improving access for disadvantaged children and using different assessment methods); spatial inclusion (whether teachers include children in all parts of the classroom); SBMC functionality, women’s participation, and children’s participation.

When ESSPIN ends in 2016, the programme will hopefully have laid foundations for a more inclusive school system.

Fatima Aboki is Lead Specialist, Community Engagement and Learner Participation in ESSPIN.

Helen Pinnock is a senior consultant with EENET. Contact: helenpinnock@eenet.org.uk

This article is based on ‘Whose learning needs to be prioritised? Inclusive education in Nigeria’, submitted to the 2015 UKFIET Conference, by Fatima Aboki, Manjola Kola and Jake Ross.