Zahra Alijah

I am a secondary-level physics teacher educator. I thought I understood inclusion and the additional support available for learners within and beyond schools. However, as a parent enabling access to education for my son, I was surprised by how naïve I felt when my role as a partner in my son’s education was undervalued.

My son’s behaviour

When we began our schooling journey, Dan1 was already active and independently minded. He showed behaviours often characterised as attention deficit hyperactive disorder or autism that I now know are related to developmental trauma, such as sensory-seeking and attachment-seeking needs. We don’t know the origins of Dan’s developmental trauma. It could be related to his adoption history.

Our first encounter with school

At age 3, Dan attended a nursery that claimed to be child-led and prioritised outdoor education. In reality, children had to follow the nursery team’s activities. The team considered Dan’s behaviour as impulsive and aggressive. He only wanted to join in on his own terms and would bump, push, and throw. Each evening, I signed incident reports about something he had done. He couldn’t cope with circle time. Now I wonder why they insisted he join in. I was asked to remove him from school because they couldn’t provide the one-to-one support needed to keep everyone safe.

Trying to get support

I approached several other settings. None felt they could provide the support Dan needed. I was advised to apply for an Educational Health Care Plan (EHCP) assessment when he was offered a place at school for Reception year (age 4). Children needing additional support in English schools are assessed for a personalised EHCP. Funding to meet the support needs identified in the EHCP is provided by the local authority. I applied well before Dan began school, but he was not assessed until two months into his first term. The school tried to prepare for him, but in September I was again told he was behaving dangerously and aggressively.

There were 60 children in the two reception classes. This must have been overwhelming for Dan given his sensory and attachment needs. The school reduced his hours. He started one hour later than the other children and went into their ‘inclusion’ room (in reality an exclusion room) before joining the mainstream class later on. He struggled with this daily transition, becoming disruptive or aggressive when he re-joined the mainstream environment. They tried to have him mix with smaller groups of children but he was disruptive.

I managed to get a place for him in alternative provision. Schools specialising in social emotional mental health needs do not enrol until Year 1 (age 5) or above. Until then I had to educate Dan at home. The local authority redirected his ECHP budget so I could access support from the local home educator group and other educational initiatives in the city. Dan flourished in many of the activities we explored during this time.

Learning new techniques at home

To support Dan’s learning at home, I accessed the local post-adoption support team who suggested using a neurosequential model of working. This is a developmentally informed and biologically respectful approach to working with children. It is not a specific therapeutic technique or intervention but a way to organise a child’s history and current functioning. I emotionally support Dan in ways often considered appropriate for children younger than him, while supporting his wider learning at a level suitable for his actual age.

Sensory integration therapy is important and takes a play-oriented approach. We use therapies like deep pressure, brushing, weighted vests, and swinging, which can calm an anxious child. I adapted my home to suit his physical needs. We have equipment to exercise and burn off energy (e.g., a small trampoline), and a hammock and weighted blanket to satisfy his need to cocoon himself. These techniques helped improve his behaviour at home and he progressed well.

Much of what I read about developmental trauma is relatable to Dan, including his struggle with transitions like leaving/entering class and his fight-and-flight responses in new or stimulating environments. Dan and I received sensory integration therapy from an occupational therapist. She helped me further develop and apply my learning. Having someone willing to listen and focus on solutions was a wonderfully positive experience.

Dan thrives in child-led, multi-sensory environments that focus on nurturing independent and collaborative learning and relationships through guidance. This approach helped him develop positive relationships with other children and educators at one of the education centres he attended during the home education stage.

Returning to school

The transition to school for Year 1 didn’t go easily. The teachers suggested that the approaches we had developed at home were detrimental to Dan’s progress. They said I was babying my son and causing all the problems.

I had felt naïve when dealing with educators at Dan’s previous settings. Now I felt empowered to speak out. Initially the teachers didn’t believe me, but as they eliminated other potential reasons for his behaviour, they started to ask me questions about what we do at home. Now we explore together the support Dan needs and try to trust each other’s knowledge.

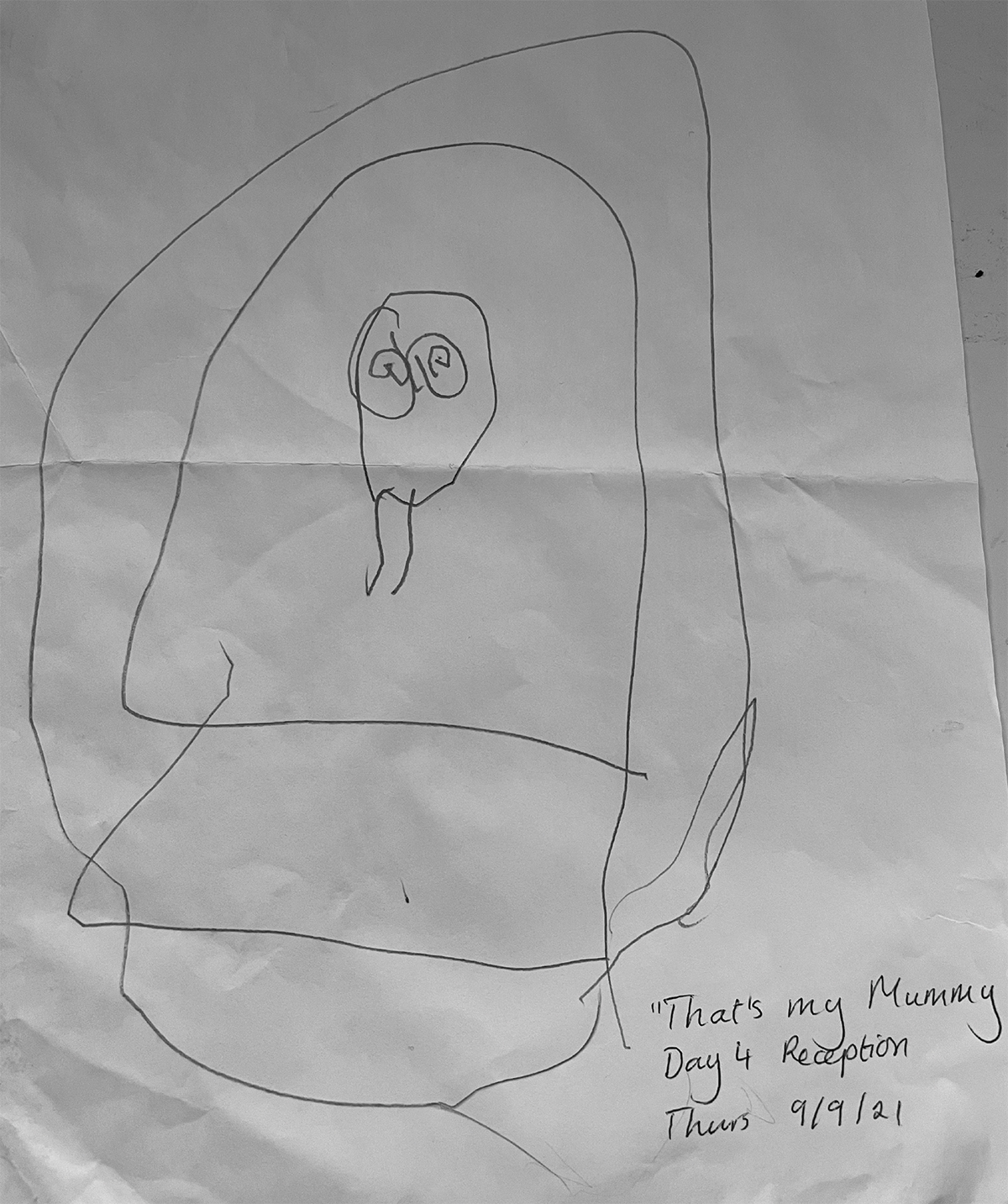

One of Dan’s drawings

Changing the system

As a teacher educator I want my students to start their careers with an inclusive mindset. As a parent I realise that much more must be done. My experiences completely changed my approach to preparing student teachers. I discuss Dan regularly as an example. We explore problems of bias and profiling, and trying to fit the child to the classroom rather than adapting the classroom to the child’s needs. I also bring developmental trauma into the lessons. We discuss how children are all very different and need unique support.

There are systemic issues I can’t fix alone. Schools are underfunded and funding may not be used in ways specified by the ECHP. It is also hard to argue a ‘good for all’ approach within a teacher education system that provides very little time to focus on inclusion.

I believe the world needs to ensure there is a Dan shaped space in it. This is what he is entitled to, like every child. If Dan needs to climb more than other children, so be it. We just need to help him learn to do so safely. It is what makes him who he is: the energy, the physicality, the adventures. And I love him for who he is.

1 Name has been changed

Zahra is a senior lecturer at the University of Manchester.

zahra.alijah@manchester.ac.uk