Newton Njoroge

Life Skills Oasis (LSO) is a not-for-profit organisation working with children from Kiandutu informal settlement in Kenya, who are at risk of, or have already dropped out of school. In this interview, Newton Njoroge tells us about the challenges and opportunities affecting their work since the arrival of COVID-19.

How did COVID-19 affect your work with children in Kiandutu?

LSO runs education programmes in Kiandutu. We run a drop-in centre that opens seven days a week. From Monday to Friday, we deliver a programme of support for children who are not in school. This includes children who are street-connected and those who are at risk of being street-connected. At weekends and during the holidays, we organise additional activities for children who go to school.

When COVID-19 arrived, schools in Kenya closed in March 2020 and reopened in January 2021. This meant nine months in which the poorest children were not able to access education, as centralised home learning provision was mainly provided through television and radio. Initially we attempted to fill the gap in their education, but government restrictions soon meant that our work was limited until September 2020, when we were able to resume our education programmes.

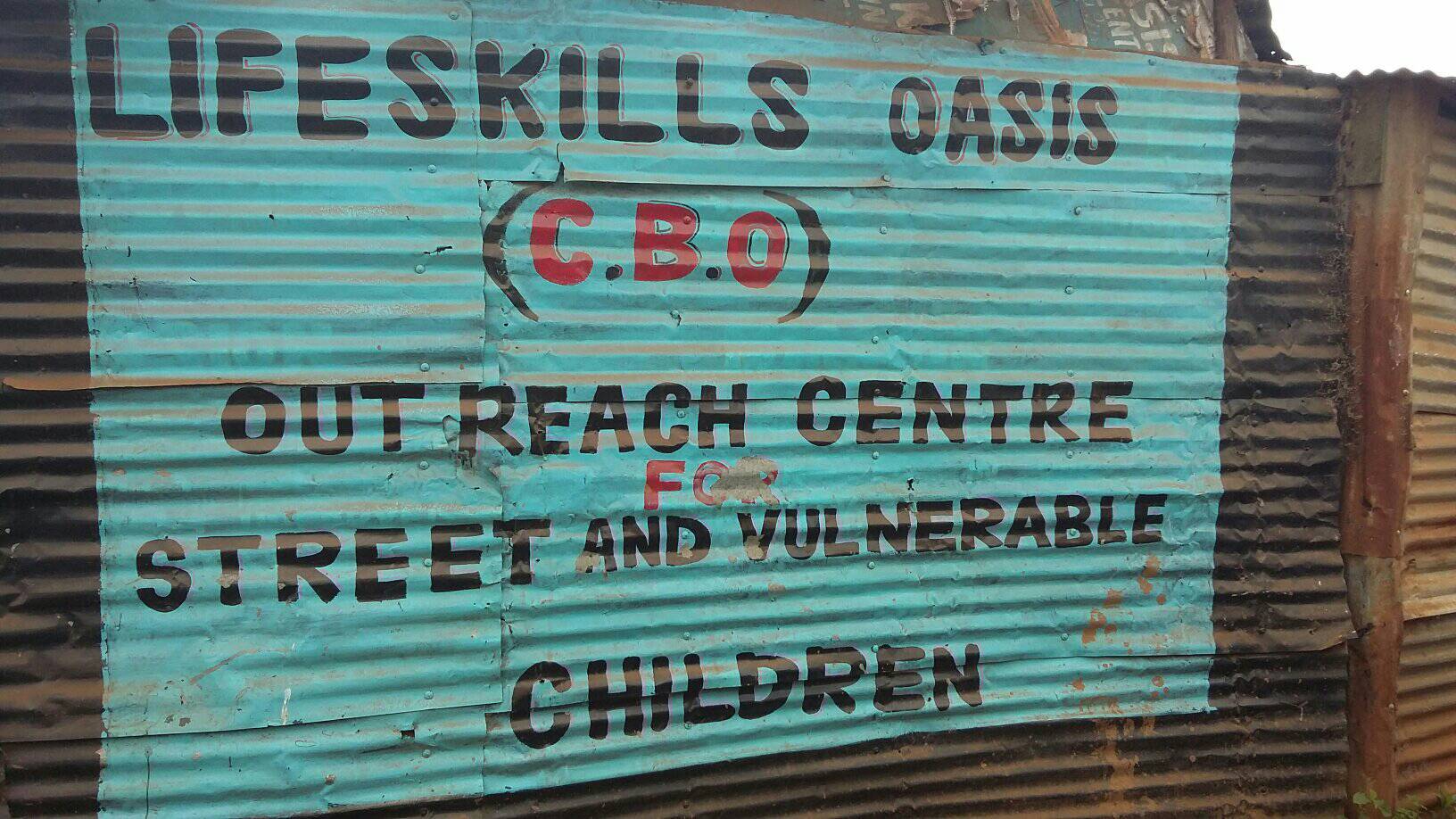

Fence around the LSO building

What have been the main challenges affecting you since you resumed your programmes?

There has been an increase in the numbers of children on the streets. This is because many parents lost their sources of income as they were unable to go to work in the informal labour market. Since life opened back up, many have not been able to find work again as there are fewer options with businesses collapsing during the pandemic. Food and fuel prices have increased in the last few months so it is difficult for the poorest families to meet basic needs.

There has also been an increase in the number of children who have been using drugs in Thika town. There are many reasons for this. The first is an increase in the range of drugs and solvents available to the children. The second is about supply and demand. The number of children on the street has increased, so there is a perceived increase in demand. With the increase in daily living costs, there is more pressure from those selling drugs to make more money. Traditionally the children we worked with used solvents mostly (such as glue) and marijuana, as it is cheaper than food and helped them to forget the difficulties they face in their situation on the street. Now cocaine, spice, and other injectable substances are more readily available. The prolonged time on the street during the nine months of school closures meant that children were more at risk of peer pressure and being targeted by people pushing drug use.

What opportunities has LSO experienced?

There has been more local government recognition of LSO and the impact of our projects. We are now a key partner for officials wanting to keep children in a safe environment and prepare them to go back to school. There has therefore been an increase is the number of referral cases from government agencies.

The local network of community-based organisations, around Thika town and the wider district, and local government has been running for many years. However, the impact of the network has always depended on the interest of individual District Children’s Officers as they chair the network during their time in post. Since COVID-19, collaboration has improved. Representation from local government entities has extended to include community chiefs, assistant county commissioners, assistant chiefs and other agencies. The improved coordination of the network has developed a better system of tracing street-connected children’s extended family members as community-based organisations are able to work together more efficiently. There has therefore been an increase in the number of calls to LSO, as network members refer the children that they encounter on the streets to LSO’s outreach centre in Kiandutu.

This sounds great, collaboration and working together are key to inclusion. Are there any issues with being part of this network?

Local government representatives recognise the role we play in supporting street-connected children to leave the street and are committed to addressing the increased number of street-connected children. This increase in the numbers of children on the street inspired the new more coordinated approach. However, these referrals are not accompanied by financial investment. Working together reduces the money that needs to be spent at a local government level as they rely on community-based organisations to fit the bill. They are therefore relying on the organisations focused on reintegration to support the children on the streets, but we have very limited resources. There is a need for greater levels of investment to support the work of the organisations who are part of the network.

What do you think needs to happen to make the system better?

Apart from financial investment, which is very much needed, there needs to be a more coordinated approach to community development. There are reasons why children are on the streets, which are as much to do with the conditions of life at home as the temptations and freedom that street-life is perceived to provide. We need to start planning holistic approaches to building awareness of the risks of street life. This would involve working with schools to develop programmes that stress the risks to the students, supporting parents to better support their children to prevent their migration to the street, and sharing the responsibility across the different organisations within the network. For example, LSO works with children on the street and in Kiandutu, while other organisations focus on inclusive education programmes and providing feeding programmes in schools. Together we could plan to develop a broader approach to our work: e.g., providing parents with income generating opportunities; supporting children’s transitions (back) into schools; and educating the public to refer street-connected children to the LSO drop-in centre and donating to the network, rather than feeding the children on the street.

Newton is the Director at Life Skills Oasis

Contact: lifeskillsoasis@gmail.com

www.facebook.com/groups/166737591342/